|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Indigenous North American FlutesWhen I first began to look at classifying flutes that originated in North America, I quickly got the sense of dealving into a rabbit-hole topic. Rather than trying to craft flutes to a generally accepted, ideal model, makers of ethnic flutes seeks to define their own style and take the instrument in their own direction. And so, the types of flutes described on this page are mostly general classes into which a particular flute can be placed. While this page lists flutes that I believe originated in North America, little is really known at how those designs were influenced by outside cultures. The topic of outside influences and originality in the context of indigenous flute design is often debated - another rabbit-hole topic. This page mostly looks at flutes in the present-day context, and from the perspective of flute makers and players. For a historical perspective on these instruments, see The Development of Flutes in North America. One fascinating area that is outside the scope of Flutopedia deals with the possibility that an instrument can be a window of understanding the culture that developed or uses the instrument. The concept that the instrument or its primary scale can affect the culture in the same way that the language developed by a culture in turn affects the continued development of that culture. OverviewThis roster of Indigenous North American flutes is broken into two main categories: North American Rim-blown Flutes. Flutes with a single tube, completely open from one end to the other where player forms an embouchure and blows against the rim of one end of the tube. The tube is typically formed either by boring a hole in a solid material, by removing soft matter such as the pith inside a branch or the nodes inside a stalk of cane or bamboo, or by commercial fabriacation methods (such a commercially available PVC tubing). North American Duct Flutes. Flutes where a narrow duct directs the stream of air to the splitting edge at the sound hole. The player may blow directly into the duct, or may blow into a chamber that is then designed to feed air into the duct. North American Rim-blown FlutesThe Anasazi FlutePresent-day Anasazi Flutes were inspired from the Broken Flute Cave flutes excavated by a team led by Earl Morris in the summer and fall of 1931. Measurements that I took of the original artifacts were published online in late 2002. Shortly afterward, makers began producing replicas and variations based on these artifacts. Dr. Richard Payne, Coyote Oldman (Michael Graham Allen), and Ken Light were early experimenters with contemporary rim-blown flute designs, and Coyote Oldman (Michael Graham Allen) was the first maker to make these instruments available to a wider audiences of flute players. For details of the early development of contemporary rim-blown flutes, see Contemporary Rim-Blown Flutes. Here are some instruments currently being offered by several makers:

One thing to note is the alignment of the finger holes. The top flute has finger holes in a stright line, while the other makers rotate finger holes 3 and 6 for easier reach by the player. Also notice that the third flute from the top has the finger holes rotated for a left-handed player (who uses the right hand for the top holes). And here are a few samples of music: Entrance (excerpt) Michael Graham Allen. Track 1 of Rainbird. Clouds (excerpt) Michael Graham Allen. Track 4 of Rainbird.

The typical primary scale for Anasazi flutes is very different from the primary scale on Native American flutes. It is also very unusual in that there is no interval of a perfect fourth from the root note. The notes shown are typical for present-day Anasazi style flutes of about 29"-30" (74-76 cm) in length:

The fingerings for the Anasazi flute on this page are a combination of fingerings shown in ([Purtill 2008]

For a detailed fingering chart on these instruments, see the Anasazi Fingering Chart page. The Hopi FluteOnce the world of rim-blown flutes was re-opened with the Anasazi flutes, makers began creating variations. Some are patterend after traditional instruments and designs, and some are entirely recent inventions. The Hopi Flute is similar to the Anasazi flute in design, but is shorter and drops hole 5 from the Anasazi Flute. (I'm using “Flute Player Numbering” from Numbering the Holes on a Native American Flute.) It is patterned after a long tradition of flutes in the Hopi culture ([Payne 1993]). Here are some instruments currently being offered by several makers:

Because these instruments are a bit shorter — about 25" (63.5 cm) in length - they are tuned higher than the Anasazi Flute. However they have a similar primary scale:

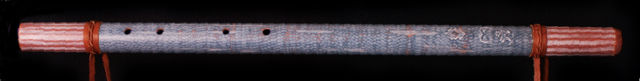

The Mojave FluteThis rim-blown flute is a present-day flute inspired by traditional flutes of the Mojave [moh-hah-vee] (also spelled “Mohave”, known as “Aha macave”, literally “People alongside water”, also pronounced [moh-hahv]). See The Development of Flutes in North America for a description of the artifacts on which the Mojave Flute is based. Michael Graham Allen began making the present-day Mojave flutes in 2007. Here are some instruments currently being offered by several makers:

The listing for the Coyote Oldman flute says that it is 24.7" (62.7 cm) in length and has a low note of B4. Here is the primary scale:

The equivalent notes to the Mohave Flute A Native American flute in F# minor will produce the same pitches as shown for the primary scale of the Mojave Flute, but most contemporary Native American flutes in any key will give a scale with the same relative notes. The Mojave Six FluteA recent variation on the Mojave fute concept came from the limited scale of the classic Mojave Flute. The highest note in the low register of the Mojave Flute a perfect fifth interval from the root note, and then there was a huge leap to the octave note in the second register. Getting more notes on a flute typically means making more finger holes, and Geoffrey Ellis of Earth Tone Flutes developed the “Mojave Six” design in 2009:

Here is the primary scale for the Mohave Six flute, based on the article by Scott August on his CedarMesa.com web site ([August-S 2009]

The equivalent notes to the Mohave Six Flute A Native American flute in B minor will produce the same pitches as shown for the primary scale of the Mojave Six Flute, but most contemporary Native American flutes in any key will give a scale with the same relative notes. The Yuma FluteThe next style of rim-blown flute we will look at is inspired by historical Yuma flutes. See The Development of Flutes in North America for the historical articacts. The Yuma flute provides us with some mysteries - We have very few authentic examples of historical instruments, probably due to the past Yuma (Quechan, Yuman, Kwtsan, Kwtsaan) tradition of burning all possessions of the deceased during the funeral ceremony ([Halpern 1997]). Michael Graham Allen calls this instrument an “Ancient Southern California flute replica”, but to my eyes it looks like the inspiration was drawn from the historical Yuma flutes:

The listing for the Coyote Oldman flute says that it is 19" (48.3 cm) in length and can be played from either end. The Maidu FluteThis description of a Maidu rim-blown flute is provided by Roland Burrage Dixon, from the Huntington California Expeditions of 1899-1904. It was published in [Dixon 1905]

The flute (Fig. 57, a) is a simple elder-wood tube, about forty centimetres in length. It has four holes; and in playing, the end of the flute is placed in the mouth, and blown partly across and partly into. There were many songs played on these flutes; but all were,

so far as is known, love-songs, or songs played purely for the amusement of the player, and the flute was not in use ceremonially at all. North American Duct FlutesThis category of flutes includes any design where a duct directs the stream of air to the splitting edge at the sound hole. No embouchure is needed to play these flutes - you just breathe into the end of the instrument. The order that I am showing for these flutes begins with the simplest form of duct flute - one where the player breathes directly into the duct - and ends with the Native American flute - where the player's breath enters a second chamber that in turn delives the air to the duct. However, I'm not implying anything about the development of the Native American flute by this ordering of flute styles. It might be that the simpler designs inspired the later Native American flute design, but that is only a conjecture.

The Papago FlutePresent-day Papago Flutes were inspired from the historic artifacts in the collection of Dr. Richard W. Payne. See The Development of Flutes in North America for the historical artifacts. (Also, please see Tribal Identification for issues relating to the name “Papago”). I know of two flute makers that are crafting these flutes:

The upper flute by Pat Partidge is in my collection, and actually has an addition thumb hole on the back of the instrument. The lower flute by Michael Graham Allen is listed by him as “Ancient Arizona flute”. The length is listed as 29.7″ (75.4 cm), although more than half of that length is taken by the slow air chamber. As with the Papago flute artifacts, the player uses a finger (typically their index finger) to form a flute by partially cover the SAC exit hole and the sound hole. It take a bit of practice, but works nicely after a few minutes. The Pat Partridge Papago flute has ridges on three sides of the nest area to make this easier. Here is an improvisation on my Pat Partridge Papago flute: PapagoImprov Clint Goss. Papago flute replica by Pat Partridge. This table shows the scale of the circa 1880 Papago flute from [Payne 1989], page 21 (the flute that Michael Graham Allen used as the model for his version of this flute) as well as the notes produced by the Pat Partridge flute in my collection:

The Papago Flute is a wonderful instrument for flute instructors who are teaching beginning players:

The Pima FluteFrom [Russell 1908], page 166: The Pima or Maricopa flute is of cane

cut of such a length that it includes two entire sections and about

4 cm. (1.6″) of each of the two adjoining. It therefore contains three

diaphragms, of which the two end ones are perforated, while the

middle one is so arranged that the air may pass over its edge from

one section into the other. This is done by burning a hole through

the shell of the cane on each side of the diaphragm and joining them

by a furrow. With such an opening in the upper section the instrument

can not be played unless a piece of bark or similar material be

wrapped over all but the lower portion of the furrow to direct the air

into the lower section. The forefinger of the left hand is usually

employed as a stop if no permanent wrapping directs the current of

air so that it may impinge upon the sharp margin of the opening into

the second section. As there are but three finger holes the range

of notes is not great and they are very low and plaintive. “Specimen c” refers to the lowest flute in this image:

Russell notes that the bottom-most flute “has an old pale yellow necktie tied around the middle as an ornament and to direct the air past the diaphragm.” He also lists the measurements of these flutes in a footnote of page 167:

“The principle of its construction is believed to be different from any known among other tribes or nations. These instruments are common with the Coco-Maricopas, and Yumas or Cuchuans, and among the tribes on the Colorado. Young men serenade their female friends with them.” Whipple, Pac. R. R. Rep. II, 52. From [USWD 1855], volume 3, part 3, page 123: Of the Pimas, Papagos, and Coco-Maricopas The Tarahumara FluteThe style of flutes from the Tarahumara culture is described in [Payne 1989], page 29-30: The Tarahumara, in the vast Barranca del Cobre east of the Yaqui, play a small beaked tabor pipe made of the cane (Arundinaria) that grows in the valleys of their vast canyon country. These flutes, usually played as tabor pipes accompanied by a large tambour (a manner attributed to Spanish influence), resemble in some respect the clay flutes of the prehistoric Mayan and Aztec civilizations. Similar flutes are currently widespread among the native cultures of Mexico. Here are some photos and an improvisation on the Tarahumara flute in my collection, from the collection of Dr. Richard W. Payne, recorded January 14, 2012. The improvisation does not use the style suggested in the quotation above by Doc Payne, but is a solo more in the style of nature imitation: Improvisation Clint Goss. Flute of the Tarahumara culture.

For background on the Tarahumara culture, and in particular the role of music in their society, see [Wheeler-R 1993]. Here is an excerpt: Music sanctifies the moment in the life of all the Tarahumaras. Our dances permeate our daily lives with joy, courage and trust in Our Creator. Our songs and dances are like prayers of thanks to bless the sick, our fields and our crops. Even the most common tasks have a higher meaning when music is in the air. When Onorúame God -created the world, He did so singing and dancing. The heartbeat of Mother Earth was the drum that accompanied Him. When we rest in the bosom of the earth we feel Her heartbeat and when the Yúmari (the sowing dance) is played we hear the pulse of life drumming to the chanting prayer of the sewer. All of our actions have musical meaning. … The Choctaw Overtone FluteThe flute of the Choctaw culture, of which I know a single example: a flute in my collection originally from the collection of Dr. Richard W. Payne. The cultural context of the flute was provided by Dr. Payne (personal communication, November 2002) with additional information from Vern Berry (personal communication, September 25, 2005).

The flute has no finger holes. It measures 17.25″ (43.85 cm) long, with the physical length of the sound chamber from the plug to the foot end of the instrument of 16.50″ (41.91 cm) and the diameter of the cylindrical sound chamber of about 7⁄16″ (0.44 cm). Because this is a relatively long sound chamber in relation to the diameter of the sound chamber, it plays easily into the upper registers. This puts it in a class of flutes known as overtone flutes.

However, a word of caution on my assumptions of how this flute was actually played: It has been pointed out that I may be over-reaching in my conjecture that this flute was played as an melodic overtone flute. Barry Higgins of White Crow Flutes (personal communication, January 13, 2012) cautioned that, regardless of how the flute can be played today (and how a person familiar with other world overtone flutes might play it), little can be said about how it was actually played in the culture. For example, the instrument may have been used simply for signaling, and not played melodically. Improvisation Clint Goss. Overtone flute of the Choctaw culture. And here are the measured pitched — basically the overtone series:

The Native American FluteAnd finally, we get to the focus of this web site, the Native American flute. There are many other pages on this site that explore the development, anatomy, and keys available for the Native American flute. In terms of variations on the instrument, there are far too many to survey or keep track of. One newsgroup on Yahoo dedicated to makers of the instrument had 3,549 members as of September 17, 2010, and many of those makers create their own variation or style of instrument. | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

To cite this page on Wikipedia: <ref name="Goss_2022_flute_types_north_america"> {{cite web |last=Goss |first=Clint |title=Indigenous North American Flutes |url=http://www.Flutopedia.com/flute_types_north_america.htm |date=7 June 2022 |website=Flutopedia |access-date=<YOUR RETRIEVAL DATE> }}</ref> |

![Pima flutes from [Russell 1908], figure 80 Pima flutes from [Russell 1908], figure 80](img/SIRIS_GN_02679B_sm.jpg)