|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Proto-Flutes and Yucca StalksWhat inspired early humans to take time out from their busy hunting and gathering schedule to blow across a hole in a hollow stick? Was there some element of their natural environment that encouraged them to experiment with an embouchure to create whistling sounds and steady tones? This page presents some ideas on “proto-flutes” — natural artifacts that might have inspired the first human explorations with the basic elements of a flute: resonating air columns, creating sound using embouchure, and possibly finger holes. Note that proto-flute theories are centered mostly on creating standing waves in sound chambers using embouchures, not the crafting of stalk flutes themselves. This is a working page, in the sense that it is a collection of related items in a line of inquiry, not a complete presentation. If you have any thoughts, ideas, information, or items to contribute, please contact me. This page of Flutopedia is the combined work of Christine Oravec and Clint Goss. Items were contributed by Michael Graham Allen and Keith Stanford, as noted below. BackgroundWork in the direction of proto-flutes was inspired by some artifacts collected by Michael Graham Allen (a.k.a. Coyote Oldman) — dried yucca flower stalks, hollow inside, with holes that were beautifully bored by some natural agent. I photographed them in November 2012. Click on any image for a larger view:

These artifacts begged some questions:

The Magic FluteIn 2013, I received a copy of The Magic Flute by Kaye Feather Robinson, now published on this site and also available as a PDF file ([Robinson-KW 2012] After I finished the stories, I noticed a yucca stalk on the floor. …

I told Peter that the teachings were over and it was time to give an offering of Flute Music. …

He saw what others did not see. He saw six small holes that tiny critters had left in the old hollow stick. …

“I think I can play the stick.” Peter surprised everyone with this statement. I thought I knew plants and plants usages. But this was new to me. In June 2015 I found this description by Peter Phippen of this potential origin for the embouchure hole, the earliest mention of which I am aware. From [Crawford 1999b]: I live in Wis[consin] and in my backyard there is a cane-like plant that bugs burrow into to hibernate for the Winter. One Spring I noticed a flute-like sound coming from one of these stalks. Upon investigating, I found that a bug had left a small hole in the side of the stalk, making a flute-like sound when the wind blew. Could early man have stumbled onto something like this? If so, the cane or bamboo flute would have come first. Perhaps the earliest flutes were one- or two-note flutes with no holes, with the second note and possibly a few overtones (depending on the length of the instrument) being achieved by over blowing. Yucca and related plantsThe group of plants that might be considered for proto-flutes includes yucca, sotol, and agave. An excellent primer on these plants can be found on The Agaves and Nolinas page of the Saguaro-Juniper web site.

These plants produce an inflorescense — a cluster of flowers arranged on a stem. The stem can be composed of a main branch or a complex arrangement of branches. The photo at the left, courtesy of Keith Stanford (Kieta [key-eh-tah]) of CherryCows Flutes shows a small yucca plant with two inflorescense stalks - an old, dried stalk and a new stalk emerging. Kieth describes this picture: Here are a couple of pictures I took last week down on my ranch by Tombstone, AZ. You can see the old stalk on top of this small Yucca, and the ‘new’ stalk just starting to come out. EthnobotanyThese excerpts from [Gibbs 2003] (pages 2-1 and 6-7) and gives some background on the ethno-botany of yucca and related plants in the San Andres National Wildlife Refuge, New Mexico: The San Andres Mountains contain five general plant communities, including desert shrub, desert riparian, grass-shrub, mountain shrub and piñon juniper. Vegetation found within the San Andres National Wildlife Refuge includes needle and thread grass (Stipa comata), gramma grass (Boteuloua spp.), mountain mahogany (Cercocarpus montanus), prickly pear cactus (Opuntia spp.), agave (Agave spp.), Yucca (Yucca spp.), and ocotillo (Fouquieria splendens). Higher elevations contain stands of piñon pine (Pinus edulis) and juniper (Juniperus monosperma). Desert willow (Chilopsis linearis) and apache plume (Fallugia paradoxa) are found around springs and major drainages ([RMC 1998]). While still speculative, several studies of the Apache Indians can be valuable in understanding prehistoric subsistence patterns. Basehart’s (1973) study ([Basehart 1973]), for example, based on ethnographic research, examines water gathering, agriculture, and place names with territorial references. The study provides a long list of usable stone, animal, and plant resources in semi-desert brush, grassland, woodland, and forest ecozones. His study strongly indicates that almost every plant was of some subsistence, medicinal, or architectural value. The four wild food crops that proved most important, primarily for food storage purposes, were mescal, datil fruit from Yucca bacatta, piñon nuts, and mesquite beans ([Basehart 1973]). The majority of all the wild foods utilized by the Mescalero are known to exist within 2 km of the bajada slope ([Johnson-M 1991]). Who drilled the holes?What creatures made those holes in the yucca stalks? Several citations from ethno-botanists provide some clues. From [Castetter 1938], page 51 ¶2: Small quantities of honey, the product of large wild carpenter bees, were occasionally obtained from agave flower stalks by the Maricopa ([Spier 1933], page 73 ¶3 — see below), while in Havasupai territory wild carpenter bees had their hives in flower stalks of dead agave ([Spier 1928], page 108 ¶3 — see below). From [Spier 1933], page 73 ¶3: Honey was occasionally obtained form the flower stalks of mescal, but these contained very little. This was the product of large bees (mŭspo'kwĭni'lyȧ, "black bee"). This classification of "bees" is rather interesting: working bees were called flies (xalyȧsmo''kwĭlyȧvi'na); another bee with a yellow back (not a hornet) was mŭspo'cilyamŏ'kkȧkwĭ'sĭc; a fourth variety, resembling a was was mŭspo'kwĭsĭ'c, "yellow bee." The nests of working bees were found and the insects killed individually, but their honey was not eaten. From [Spier 1928], page 73 ¶3: Wild bees hive in dead logs and the flower stalks of dead mescal. According to Brad Young of 4 Wind Flutes, (information he provided in an open forum for flute makers on May 4, 2013): In the desert, carpenter bee females nest in sotol and various yucca and agave bloom stalks, or they may take up residence in dead tree trunks and limbs, firewood or wooden structures. Beginning in the spring, a female, like a miniature carpenter, will burrow a half-inch-diameter horizontal tunnel so perfectly circular that it could have been produced by a power drill. She leaves, in her wake, a small pile of sawdust beneath her construction site. Within her tunnel, which extends perhaps six to 10 inches deep into wood, she excavates a gallery where she deposits her eggs. Here is a photo of a nest, or “gallery”, created by carpenter bees in a 2×4 piece of wood:

Here is a photo provided by Keith Stanford from his Native Yucca Stalk Flute Making Manual ([Stanford 2012]) showing “a perfect, insect-made bore, except that it is too narrow for what I wanted, so I gouged it out wider. The yellow in the photo is the natural insect bore”:

Keith StanfordFlute maker Keith Stanford (Kieta [key-eh-tah]) of CherryCows Flutes provided a first-person experience with sotol plants and their inhabitants. From an email on May 3, 2013: Last summer, I harvested about a dozen Yucca-stalks and was driving down the Interstate back to Tucson. I looked in the rearview mirror and saw what appeared to be a black bat hovering near my ear. After trying to control the resulting swerve across both lanes of the highway, I was able to get my SUV stopped and I bailed out of my vehicle. Now remember, there are cars speeding by at 75 MPH and it is about 105 degrees in the shade … I was in the sun … and I am running around the vehicle like a madman trying to open all the doors.

Later in 2013, Keith captured one of the critters on his cell phone. From an email on October 28, 2013: I was out harvesting Sotol-stalks and after I got the batch home I commenced to cutting them all to the proper length for flutes. Evidence for Yucca Flutes in the Archaeological LiteratureThis section is an analysis by Christine Oravec, version 3 dated April 2, 2014. Published reports of flutes made of yucca stalks may be found in the work of archaeologist Walter Hough. In 1901 and 1905 he accompanied expeditions to the Mogollon area of west central New Mexico. Two organizations sponsored the expeditions. The first was a group of private individuals that later founded the Southwest Museum of the Archaeological Institute of America, at that time located near Pasadena CA. The second was the United States National Museum, a division of the Smithsonian Institution in Washington, DC. The artifacts collected during the expeditions were distributed between the two organizations. After the 1905 expedition Hough returned to the USNM. He eventually became head curator of anthropology and spent the rest of his career documenting the Smithsonian’s vast collection of Native American artifacts ([Pavesic 1999], page 140). Hough published two reports mentioning yucca flutes unearthed during the expeditions. The first report included only a brief statement about the instruments themselves:

“Music was also a pastime of these ancients, who used flutes of reed and yucca stalks”

([Hough 1907], page 27). Nevertheless his identification of the artifacts as made of yucca was credible. Hough was an ethnobotanist as well as an archaeologist, and he published several articles on succulents and their use among such Southwestern native tribes as the Hopi ([Judd 1936] In 1914 Hough published another report for the Smithsonian ([Hough 1914]) that commented upon and illustrated artifacts of flutes. These were specifically identified as excavated at the Tularosa and Bear Cave sites in the Mogollon region. Under the title “Flute Pahos” he included detailed descriptions and pictures of flutes made of cane, reed, yucca slats and yucca fibers. In particular, the illustration shown in Figure 330 represented a flute paho made of a single hollowed-out yucca stalk with no identifiable breath or finger holes.

Note: In this section of the report Hough frequently used the term “paho.”

Otherwise known as “prayer sticks,” pahos were solid pieces of wood or vegetal fiber decorated with feathers, twine and paint. They were primarily used as ceremonial objects. The Hopis, for example, inserted small sticks made of willow or cottonwood topped with feathers into the ground in front of altars during the Flute Ceremony. These sticks functioned as symbolic flutes ([Payne 1993], pages 19 and 55–56). In 1950, Paul S. Martin conducted another excavation of the Tularosa cave complex and confirmed the presence of flutes made of cane. See The Tularosa Cave Flutes. More information might be obtained from Walter Hough's original Field Notes ([Hough 1905]). More Literature ReferencesFor additional references, see the section of citations on the Ethnobotany References page, in particular [Hough 1897] ArtifactsNMM 4044National Music Museum, Vermillion, South Dakota. #NMM 4004. Courting flute, Apache Nation, Southwestern United States, 19th/early 20th century. End-blown, notched flute of vegetal stalk, perhaps the bloom stalk of an agave, a yucca variety, covered in thinly-processed leather. Geometric designs cover leather surface. Cut cowrie shells and colored beads are suspended from leather tassels. Attached leather straps for carrying and storing. Played by covering all but the notch with the mouth and directing the air stream to split over edge of wood. Attached to the flute are thin leather strips bound with wrapped brass wire, to which are attached blue “padre” beads, purple Venetian beads, and cowrie shells (with tops cut off). Arne B. Larson Collection, 1979. See the web page on this artifact on the National Music Museum web site for more information on the blue “padre” beads and other information:

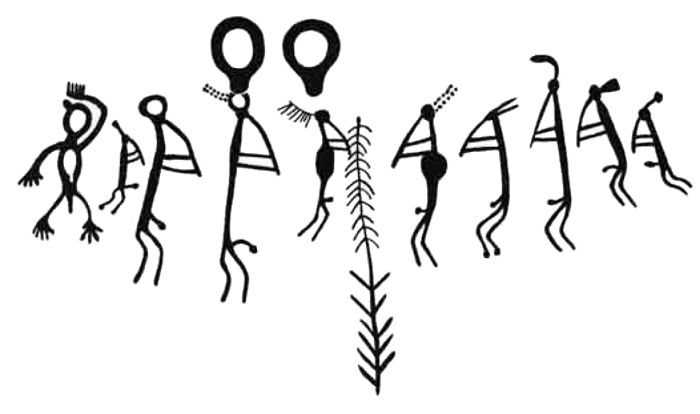

IconographyThis section surveys all rock art images that we know of that juxtapose flute players with plants that appear similar to yucca. This image of a rock art panel near the San Juan River, near Bluff, Utah was published in [Manning-SJ 1992], figure 20. Manning states that the plant image “resembles” yucca. It was also analyzed in [Slifer 1994], figure 148, who state (pages 89–90) that: [O]ne interesting petroglyph panel portrays a row of figures: five fluteplayers to the right and four fluteplayers to the left of a centrally placed plant form (yucca in bloom?). All nine fluteplayers are phallic and wear and unusual variety of head-dresses; one is humpbacked. Christine Oravec notes that “From my personal experience, it is difficult but not impossible to distinguish rock art depictions of plants according to species. Most are corn. Having seen well-defined corn depictions, however, and noting the sheer number of flower and leaf stalks in this depiction and their relative directions with relationship to the main stalk, I think Slifer and Duffield made a pretty good guess.”

Here are images based on Christine Oravec's recent publication Yuccas, Agaves, Butterflies and Flute Players: The Significance of San Juan Basketmaker Rock Art in the Flower World ([Oravec 2014]). These images are based on the figures indicated, but re-composed from the original photographs:

Narratives

Can narratives tell us something about proto-flutes? Here are six narratives in the Origin of the Native American flute section of the Narratives page on this site, and a very brief summary of the source of the flute:

Next StepsOne of the next steps in this line of inquiry would be to try some basic experiments. The idea would be to set up yucca stalks with naturally bored holes and a hollow core in a controlled environment where a wind could be driven at the stalks at varying angles and speeds.

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

To cite this page on Wikipedia: <ref name="Goss_2022_yucca"> {{cite web |last=Goss |first=Clint |title=Proto-Flutes and Yucca Stalks |url=http://www.Flutopedia.com/yucca.htm |date=7 June 2022 |website=Flutopedia |access-date=<YOUR RETRIEVAL DATE> }}</ref> |

![[Hough 1914], page 125 [Hough 1914], page 125](img/Hough_1914_CultureOfTheAncientPueblos_p125_sm.jpg)

![[Hough 1914], page 126 [Hough 1914], page 126](img/Hough_1914_CultureOfTheAncientPueblos_p126_sm.jpg)

![[Hough 1914], page 127 [Hough 1914], page 127](img/Hough_1914_CultureOfTheAncientPueblos_p127_sm.jpg)